Insane in the In- Game: A Series on the Psychology of Gaming

Don’t Mess With the Flow, no no

Hello internet, my name is Arriane, and I like Psychology, very much, in fact I borrowed a load of money and studied it for a few years. During this time, I conjoined this interest with another big love of mine, gaming, to form some kind of mutant love of a thing called Cyberpsychology, the study of the human mind and machine, and all the complexities that lie within. In particular, I’m fascinated with the attachment between game and gamer, which I hope to shed some light on in this series, so, as a certain hat wearing friend of Friendship Kingdom once said, hold on to your butts!

Let us begin this foray into the meat inside of our skulls with the basics, have you ever played a game that took you gently by the hand, and laid you down for some sweet cyber action? Well, I’m sure most of you have, and indeed with most games, but have you ever wondered how and why these games captivate us so much?

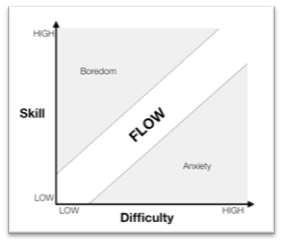

The very design of the games we play are crooks used to drag us into this alternative reality, if we bring it down to base level, many of the ground-breaking games we play have clear goals with a ruleset, us humans can only process so much information visually and auditorily, so if we’re hit with a mass of complex and confusing story with unclear direction or other distractions, we’re going to lose focus and interest in the game. Psychologist Csikszentmihalyi coined the theory of cognitive flow, the perfect mix to gently caress and envelop us poor saps into that juicy new release, we need to be able to fully absorb what the game is telling us, which maintains an equilibrium of states, or flow to keep our attention.

The difficulty of the game we’re playing can also throw us, and the controller across the room, and snatch away that immersion we were enjoying so empathically just minutes before. Stress can have a detrimental effect on our capabilities of gameplay, have you ever played a game that you’ve just had to quit because it was a big load of rage inducing bollocks, leeching away the enjoyment of the very thing you use for enjoyment? We all have different experience levels in real life (who knew?), what might be easy for some is virtually impossible for others, be it due to the games genre or how well versed the player is in games, if we hit a brick wall that we can’t break down, we’re going to get to the point where we stop, bloody knuckled and shamed.

It should be noted at this point, that there is a juicy zone for each player where arousal (not that kind, dirty) and stress states can combine for the perfect performance, we don’t all fit perfectly onto the bell curve, but that tension can make the reward even greater, that rush we feel when we’ve managed to hit the goal within the time limit, or kill that boss with only one heart container remaining is very satisfying, that reward strengthens motivation to continue playing, potentially leading to addiction, but let’s leave that for another article hm?

Anyway, to combat the number of rage quitters destroying their gaming equipment, some game designers incorporate difficulty levels so us useless plebs can be faux Gods on easy, and you pros can be actual Gods on insane mode. We all get rewarded then, we can give ourselves a hearty pat on the back for finishing the game, for getting those trophies, or exclusive gear in game to wield like a cyber dick, hurray! This also keeps us on the pulse of that game, eager for more, after all, you’re more likely to purchase the next game in the series if you completed the previous offering.

Anyway, to combat the number of rage quitters destroying their gaming equipment, some game designers incorporate difficulty levels so us useless plebs can be faux Gods on easy, and you pros can be actual Gods on insane mode. We all get rewarded then, we can give ourselves a hearty pat on the back for finishing the game, for getting those trophies, or exclusive gear in game to wield like a cyber dick, hurray! This also keeps us on the pulse of that game, eager for more, after all, you’re more likely to purchase the next game in the series if you completed the previous offering.

The third characteristic of Csikszentmihalyis’ idealistic flow state environment is player feedback on performance, be it through an XP bar, the decapitation of the enemy, or the opening of a hidden passageway, this continuous feedback of action and outcome drives our innate learning and conditioning mechanisms, making us more likely to keep that engagement with the game. Now, there is a sweet spot for this action and reward, if the feedback is immediate, during and once the action is completed, we won’t feel the same gratification, the golden rule is 300ms, specific, I know, if the feedback begins during the action and ends after the action is completed, this too feeds our motivation to play, because who needs daylight anyway?

The final characteristic, and one I’ve brushed on slightly already is how much information is being presented to us during the game, a cluttered UI, or obscene graphics that can blind us like we’ve just opened the Ark can prevent the gamer from distinguishing between the important stimuli and tosh, inhibiting the ideal flow state, how can we learn and achieve when we’re busy figuring out how the fuck we equip a weapon, or getting owned because we didn’t see the enemy approach? Although I’m not disputing that gorgeous graphics can reel us in, and are often a reward in themselves, it’s important for those developers to maintain an equilibrium that doesn’t impact gameplay, a beautifully designed game does not necessarily make a good game.

So, there you have it, games that have solid goals, manageable rulesets, diverse difficulties, minimal distractions and a good feedback loop are all the magical ingredients to create and maintain cognitive flow, this flow is what feeds us, and keeps us in the game. Of course, the majority of the games we play already have taken these golden rules on board in the creation of their electronic children, perhaps you want to make a game, if that is indeed the case, remember the psychology of the design, and don’t fuck it up.

References:

Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience (2008), by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, published by Harper Perennial Modern Classics